We now flash forward twenty-five years to the case of the day, Bollea v. World Championship Wrestling, Inc., 271 Ga. App. 555, 558 (Ga. Ct. App. 2005). Bollea sued for defamation over comments another wrestler made on air which went outside of the script for an otherwise scripted fued between Hogan and the other wrestler. The court found:

Wrestling is a form of entertainment and the characters involved are fictional. ... During his "promo" speech, Russo never mentioned Bollea, only the fictional character Hogan. Further, according to Russo's affidavit, he made this speech solely as his on-air character to advance the story line and thus to lead in to the final match of the event between Jarrett and Booker T. In light of the above, the trial court correctly concluded that the allegedly defamatory speech could not be understood as stating actual facts about Bollea.

(Emphasis added). Id. at 558.

This decision is made on the premise that defamation must be "of and concerning" the plaintiff, the same basis for the rejection of cases alleging defamation of large groups instead of identifiable individuals. However, this case is truly a stunner (I could be so crass as to pun, and call it a "stone cold stunner"). There is precious little precedent to support this finding. In Perry v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., 499 F.2d 797 (7th Cir. 1974), Lincoln Theodore Perry, the actor who had made his fame under the stage and screen name of Stepin Fetchit, sued the producers of a documentary which had Bill Cosby suggest that the character had damaged views of Blacks. There, the Seventh Circuit stated:

Perry contends that Cosby's statement was false in that he was neither lazy nor stupid, [and] that the characters he portrayed in the movies never shot craps or stole chickens.... The record shows that, first, Cosby did not say that Perry was lazy or stupid but that the characters he portrayed represented such a "tradition." Second, the commentary did not state that Perry shot craps or stole chickens...

Id. at. 799. In Feche v. Viacom Int’l, Inc., 233 A.D.2d 125 (N.Y. App. Div. 1996), where an MTV personality known as 'Kennedy’ called the plaintiffs "whores," the court found that the statement "was not 'of and concerning’ plaintiffs, and is therefore nonactionable as libel," because "[a]n average viewer would not, taking into account the context in which the remark was uttered, perceive that 'Kennedy’ was making a factual statement about plaintiffs, but rather was indulging in hyperbole and protected opinion about the fictional characters that plaintiffs were portraying." Id. (emphasis added).

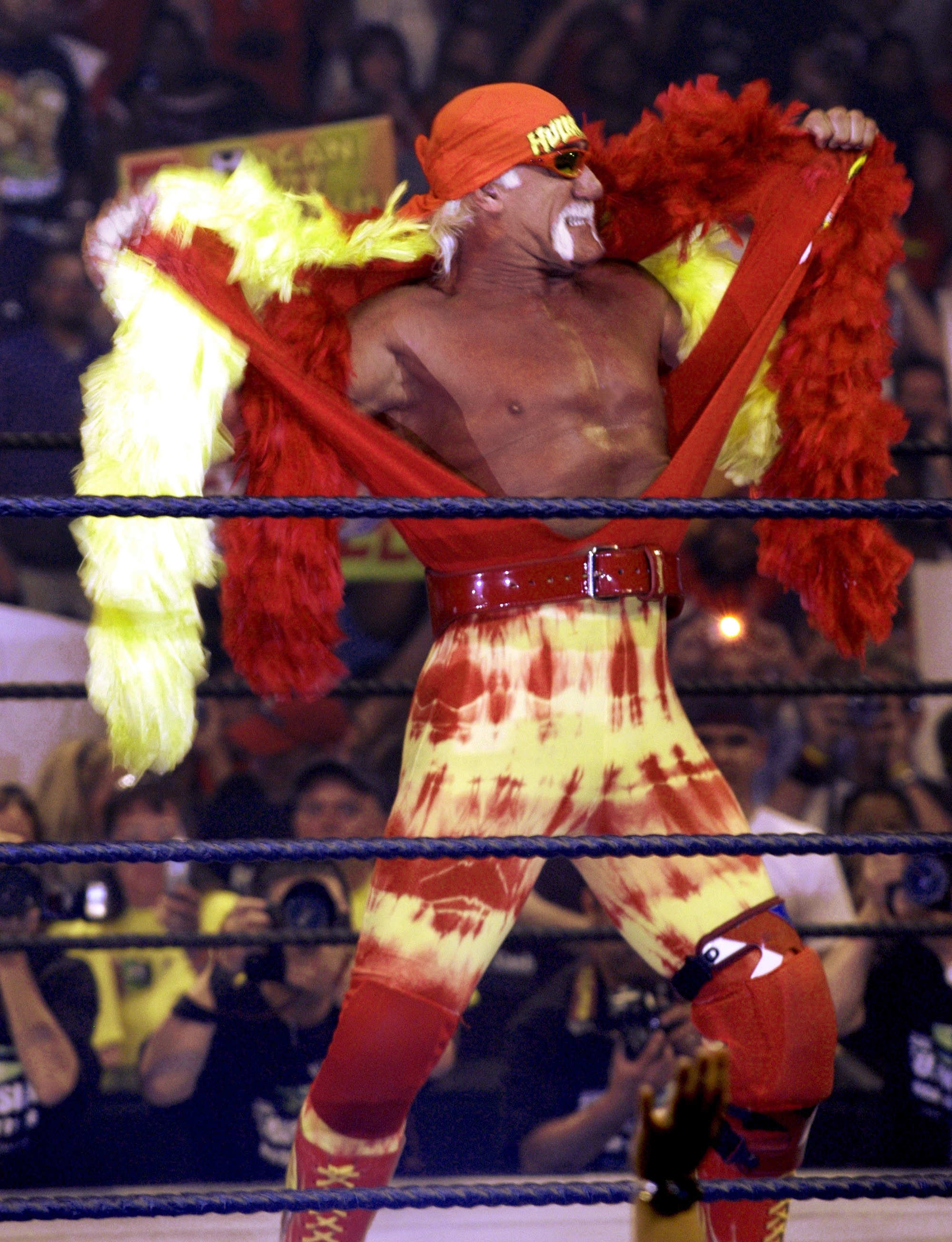

However, in none of these cases can it possibly be contended that the "character" is as closely identified with the actual person as Hulk Hogan can claim to be. Indeed, in the very year that this case was decided, VH1 premiered its reality show, "Hogan Knows Best," identifying not only the wrestling star, but his entire family by the surname "Hogan." Although the children are really named Nicholas Allan Bollea and Brooke Ellen Bollea, the world knows them all as members of the Hogan family. Surely, therefore, the type of injury that is intended to be addressed by the law of defamation, particularly damage to standing in the community, is even greater when a defamer slanders "Hulk Hogan" than when the same commentary is announced towards the obscure persona of "Terry Gene Bollea"!

All images used in this blog are from the Wikimedia Commons.